the vagus nerve: a neuroscientist's perspective

Professor Gaby Badre gives a neuroscientist's perspective on the crucial component in the parasympathetic nervous system and his take on nervous system care.

a neuroscientist’s perspective

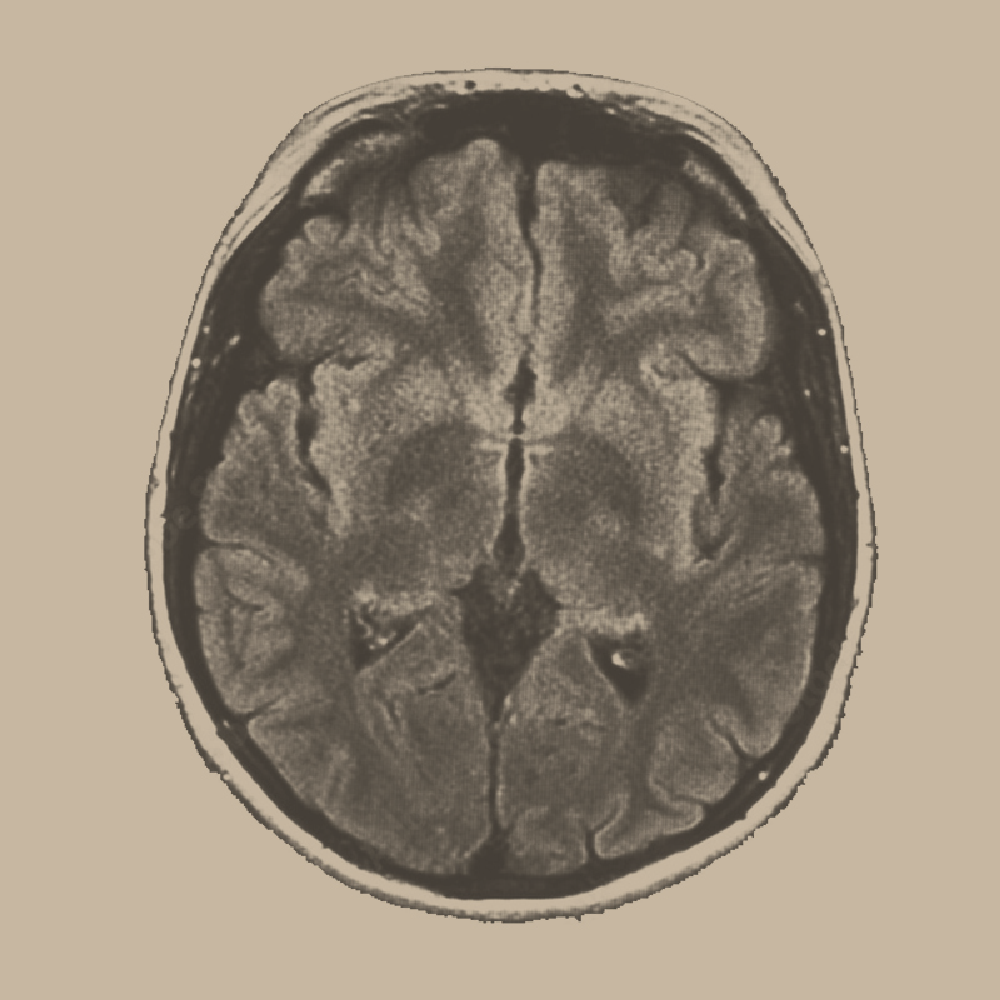

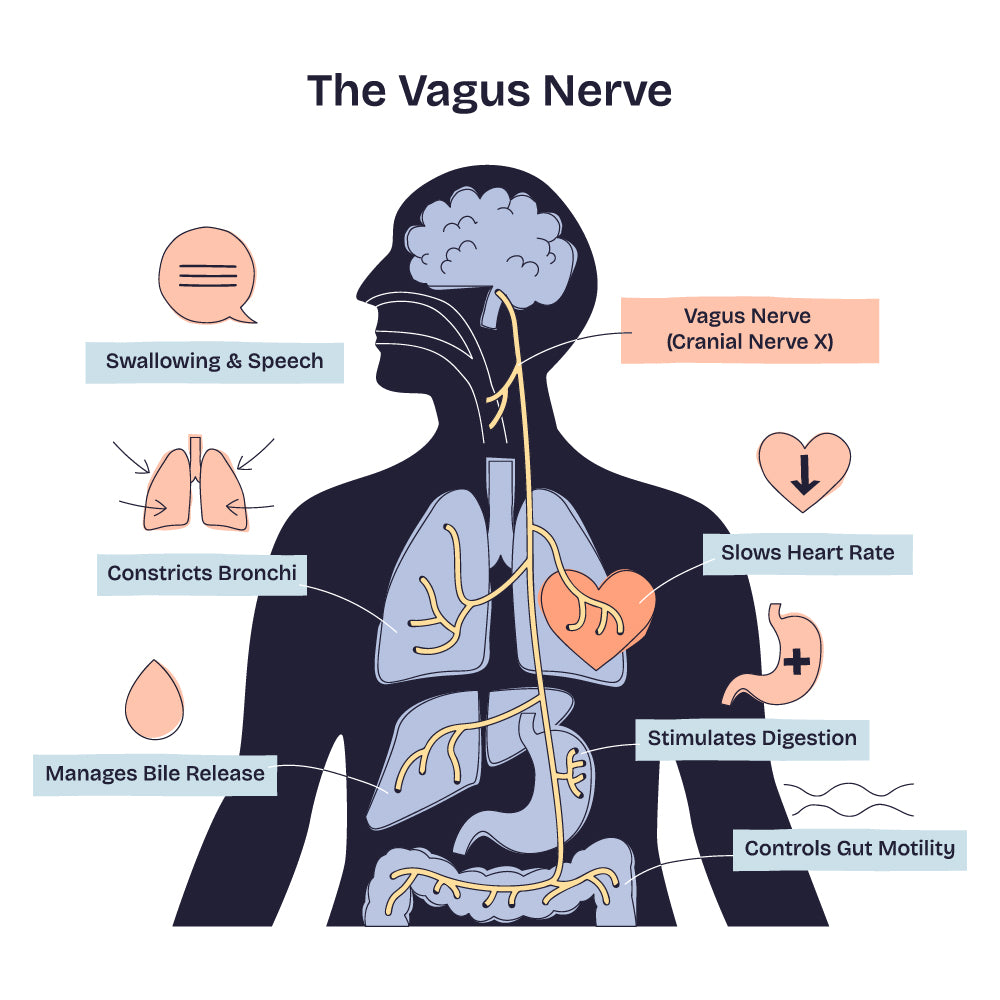

The vagus nerve represents one of the most fascinating and clinically significant components of the nervous system. The nervous system is the body's communication network, consisting of the central nervous system (CNS) - the brain and spinal cord - and the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which regulates involuntary functions such as heart rate, digestion, and breathing. The ANS has two main branches: the sympathetic system, which prepares the body for action (fight-or-flight), and the parasympathetic system, which promotes rest, recovery, and digestion (rest-and-digest).

The cranial nerves connect the CNS to the head, neck, and several internal organs; they are 12 pairs that emerge directly from the brain or brainstem. Among them, the vagus nerve (the tenth cranial nerve) is one of the most complex and longest nerves in the body. It is the principal player in the parasympathetic nervous system, forming a superhighway between the brain and nearly every major organ of the chest and abdomen, including heart, lungs, gut and liver.

What makes the vagus particularly interesting from a neuroscience standpoint is its bidirectional communication. While the focus is often on 'efferent' signals from the brain to the body, about 80% of vagus nerve fibres are 'afferent', carrying sensory information from the body back to the brain, reporting the state of internal organs.

This ascending input is essential for maintaining physiological balance, homeostasis, by enabling the brain to monitor and adjust heart rate, digestion, respiration, inflammation, and overall general arousal.

Through its extensive connections with limbic and cortical structures, this interoceptive stream also shapes emotional states, guides decision-making, modulates stress responses, and even contributes to memory consolidation.

In this way, the vagus nerve illustrates the deep inseparability of bodily states and mental processes, while acting as a physiological counterbalance to the sympathetic "fight-or-flight" system.

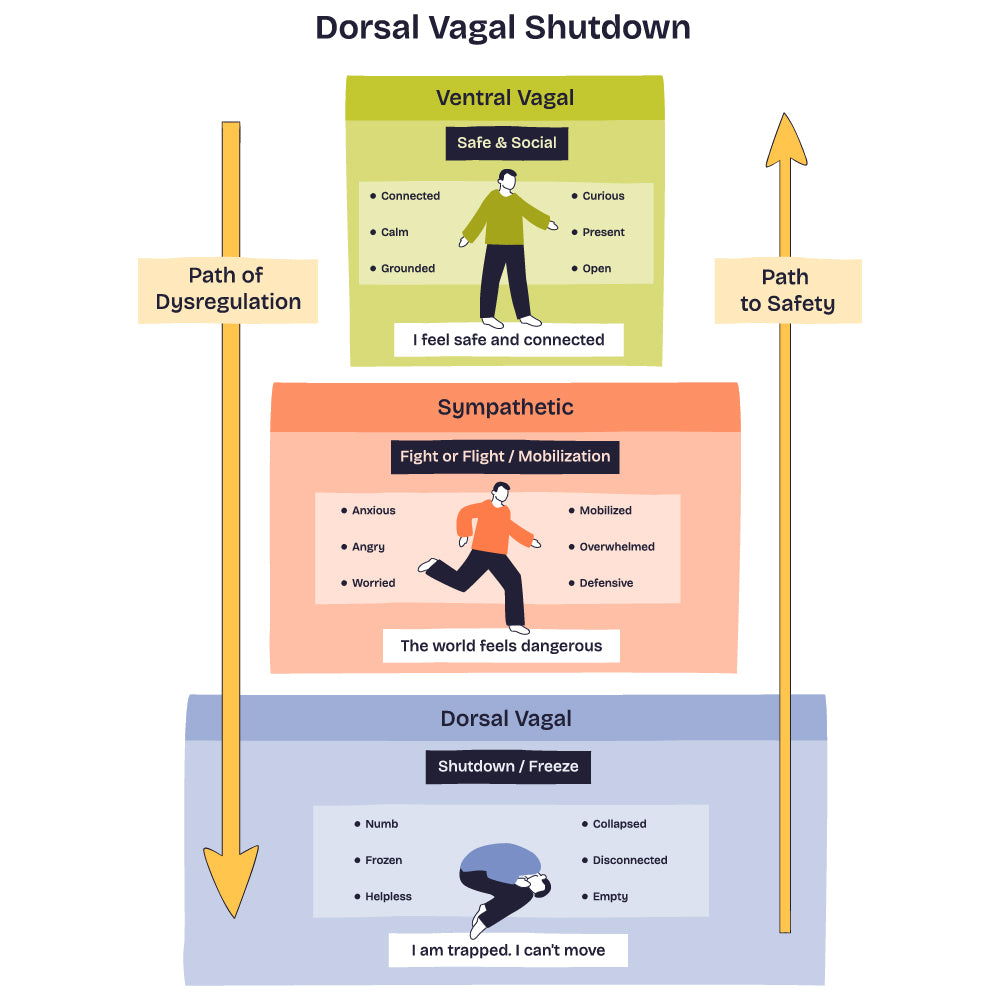

polyvagal theory

Modern neuroimaging and electrophysiological studies have shown that vagal activity is related to emotional regulation, resilience to stress, and social engagement. This underlies Stephen Porges' "Polyvagal Theory," which views the vagus nerve as a key mediator of safety, social connection, and threat responses. This theory proposes that the vagus nerve has evolved to include distinct ventral and dorsal pathways associated with different behavioural states: the ventral vagal complex, related to social engagement and calm states, operates through myelinated fibres, enabling rapid response. The dorsal vagal complex, linked to immobilisation responses, uses unmyelinated fibres and represents a more primitive defensive system. Proving vagal tone serves as a biomarker of parasympathetic regulation and adaptability.

why is the vagus nerve so important to neuroscientists?

Neuroscientists are interested in the vagus nerve because of its role in maintaining internal balance (homeostasis), influencing brain health and adaptability (neuroplasticity), mental health and inflammation.

vagus nerve and microbiota

Accumulating evidence suggests that specific gut microbiota exhibit antidepressant-like behavioural effects and can regulate neurogenesis and the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the hippocampus. The precise mechanisms underlying these effects are not yet clear. However, the vagus nerve is one of the primary bidirectional routes of communication between the gut and the brain and thus may represent a candidate mechanism. Recent findings suggest that vagal nerve activity influences neurogenesis and BDNF mRNA expression in the adult hippocampus. While the gut microbiota can influence brain function through endocrine, immune, and metabolic routes, the vagus nerve is the fastest and most direct neural channel. Afferent fibres detect luminal nutrients in the gut, mechanical stretch, inflammatory mediators, microbial metabolites, and enteroendocrine hormone release (CCK, GLP-1, PYY, serotonin).

Gut microbes can modulate vagal activity through several mechanisms, including their metabolites, which are neurotransmitters produced by bacteria (GABA, serotonin precursors, tryptophan metabolites). Enteroendocrine cells form "neuropods", which are axon-like extensions of the cell that form direct synapses with vagal afferents, allowing the gut to send signals to the brain within milliseconds. It acts like a sensory neuron of the gut, rapidly translating nutrients and microbial metabolites into neural activity. Microbes can change the hormone output of these cells. Immune signals from the gut, such as inflammatory molecules, cytokines and mast-cell mediators, can activate the vagus nerve and trigger the body's anti-inflammatory reflex. Also, the gut microbiota can alter how enteric (gut) neurons fire, thereby affecting the messages they send to the brain via the vagus nerve. The Enteric Nervous System (ENS), often called the "second brain" of the gut, is an extensive network of neurons embedded in the walls of the digestive tract that can operate independently of the brain and spinal cord.

ENS-vagus interactions refer to the continuous communication between the enteric nervous system and the vagus nerve, through which gut activity and signals are relayed to and from the brain. Microbiota modulate the excitability of enteric neurons, altering information sent to vagal afferents. The vagus nerve integrates microbial and metabolic information into autonomic regulation, emotional processing, arousal and homeostasis. This means that microbiota–vagus nerve interactions can modulate stress and anxiety responses, mood and emotional regulation, sleep, and Circadian autonomic balance. It can also influence appetite regulation, as microbiota influence the vagal-microbiota sensing pathways that regulate hormones – ghrelin, GLP-1, leptin sensitivity and reward-related eating patterns. It is shown to affect pain perception/ visceral hypersensitivity/IBS. IBS and functional GI disorders are characterised by altered microbiota composition, vagal afferent sensitisation, and disturbed brain-gut autonomic signalling. In animal studies, sectioning of the vagus nerve prevents many microbiota-induced behavioural effects, which is strong causal evidence.

vagus nerve efferents and microbiota

While "afferent" effects dominate, "efferent vagal" activity also indirectly shapes the microbiota, impacting gastrointestinal motility, acid secretion and bile flow, mucosal immune regulation, and the anti-inflammatory reflex (cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, thereby proving that vagal tone influences microbial ecology.

vagus nerve and inflammation

The vagus nerve is a key regulator of inflammation through the "cholinergic anti-inflammatory reflex," where vagal "afferents" sense immune signals and vagal "efferents" suppress cytokine release from macrophages via acetylcholine acting on α7-nicotinic receptors. Gut microbiota, immune mediators, and ENS activity all influence vagal firing and therefore the strength of this anti-inflammatory control. Low vagal tone (typically reflected by low HRV) is associated with higher systemic inflammation, while stimulating the vagus (via VNS, slow breathing, meditation, cold exposure, or exercise) enhances parasympathetic output and helps reduce excessive inflammatory responses.

NTS-LC/PFC communication

This refers to the information flow from the "Nucleus Tractus Solitarius" (NTS) to the "Locus Coeruleus" (LC) to the Prefrontal Cortex (PFC). This is one of the most essential autonomic, cognitive, and emotional pathways in the brain. NTS–LC/PFC communication is the neural pathway through which vagal signals from the body influence arousal, mood, attention, and executive control in the cortex. Dysregulation of NTS–LC/PFC communication disrupts the brain's control of stress, attention, and autonomic balance, contributing to conditions such as anxiety, PTSD, depression, ADHD, chronic stress, IBS, Parkinson's disease, and sleep disorders. In essence, when this vagal–noradrenergic–prefrontal pathway malfunctions, both emotional regulation and bodily homeostasis become unstable. It is also a key mechanism behind VNS therapy, meditation and breathwork, interoception-based treatments, and microbiota-modulating interventions.

clinical context

Research suggests interactions relevant to depression and anxiety, IBS / functional dyspepsia, metabolic syndrome, Parkinson's disease prodrome (gut-first hypothesis; α-syn propagation via vagus), sleep disorders and vagal imbalance. The idea that misfolded α-synuclein might travel from gut to brain via the vagus (Braak's hypothesis) has strong experimental support in rodents and mixed evidence in humans. According to Braak's hypothesis, an unknown pathogen (virus or bacterium) in the gut could be responsible for Parkinson's disease (PD) originating in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and similar associations have been established for Alzheimer's disease (AD) and cerebrovascular diseases (CVD).

approaches to nervous system care: how to assess vagal tone

Vagal tone refers to the activity level of the vagus nerve and is measured by the gold standard of systems, including:

- Heart rate variability (HRV). Higher HRV generally indicates better vagal function and resilience.

- Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia (RSA). This is the natural increase in heart rate during inhalation and decrease during exhalation. The strength of this rhythm reflects vagal control over the heart.

- Biomarker analysis: inflammatory markers (IL-6), stress hormones (cortisol), gastric function (IBS, reflux)

- Behavioural & Cognitive Assessments: Questionnaires on mood, anxiety, digestive health, and social engagement provide context for the objective data. The vagus nerve is heavily implicated in social connection and emotional regulation, as described in "Polyvagal Theory".

how can the vagus nerve affect everyday life?

When vagal signals increase, the brain's alertness system (LC) becomes more precise, helping with focus and mental clarity. When vagal tone calms LC activity, it reduces anxiety, stress, and overthinking. Strong vagal input helps the prefrontal cortex (PFC) stay in control, improving emotional balance and decision-making. In everyday life, vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) can reduce depression, PTSD symptoms, and improve attention. Slow, deep breathing boosts vagal activity, which calms the brain and sharpens thinking, while stress weakens vagal signalling, leading to LC overactivation and poor emotional control. Changes in gut microbiota can shift vagal signals and influence mood, cognition, and stress resilience.

Chronic vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) can help normalise gut motility, reduce inflammation, modify microbial composition, and improve mood via increased NTS-LC/PFC communication through which vagal signals from the body influence arousal, mood, attention, and executive control in the cortex. This opens the door to microbiota-autonomic interventions, including diet, probiotics, and neuromodulation.

evidence-based interventions to support the vagal nerve

deep breathing

Practising slow, diaphragmatic breathing (particularly with prolonged exhalation) stimulates the vagal afferents in the thoracic region, increasing HRV.

exercise

Consistent, moderate aerobic exercise improves vagal tone and reduces inflammation. It is one of the most potent ways to naturally increase HRV and vagal tone over the long term. Gentle rhythmic movement, such as walking, yoga, or tai chi, supports vestibular and proprioceptive integration through vagal–brainstem networks.

probiotics

Healthy gut microbiota supports vagal signalling.

humming, gargling or singing

Vibrations from vocal cords stimulate vagal afferents from the pharyngeal and laryngeal branches of the vagus nerve, providing direct stimulation.

social connection

Positive social interactions, touch (affective touch), and hugs boost vagal activity.

cold exposure

Taking cold showers or splashing the face with cold water activates the "diving reflex", engaging the vagus nerve.

advanced therapies

Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS)/Non-invasive VNS (nVNS)

Devices that deliver a mild electrical current to the cervical branch of the vagus nerve are of high interest. While approved for epilepsy and depression, they are now being explored for PTSD, Alzheimer's and more.

biofeedback

Training to consciously control physiological functions linked to vagal activity.

mindfulness/meditation

Practising mindful breathing and meditation is shown to increase vagal tone and reduce stress biomarkers.

lifestyle and environment

sleep

The vagus interacts with brainstem nuclei involved in arousal and sleep–wake regulation. Consistent sleep cycles, daylight exposure, and sensory grounding help stabilise autonomic rhythms. Poor sleep disrupts vagal function; it is essential to prioritise consistent, restorative sleep.

diet

Consuming a diet high in fibre, polyphenols and omega-3 supports gut health and vagal signalling.

stress management

Chronic stress degrades vagal tone; mindfulness and nature exposure may help.

With all the above considered, the vagus nerve represents a critical interface between brain, body, and behaviour. While widespread interest in the vagus nerve has sometimes exceeded scientific evidence, current neuroscience supports the role of parasympathetic regulation in health and well-being. For clinicians and individuals, the available data support modest, consistent lifestyle practices that enhance vagal tone as part of a broader strategy for nervous system optimisation and overall health.